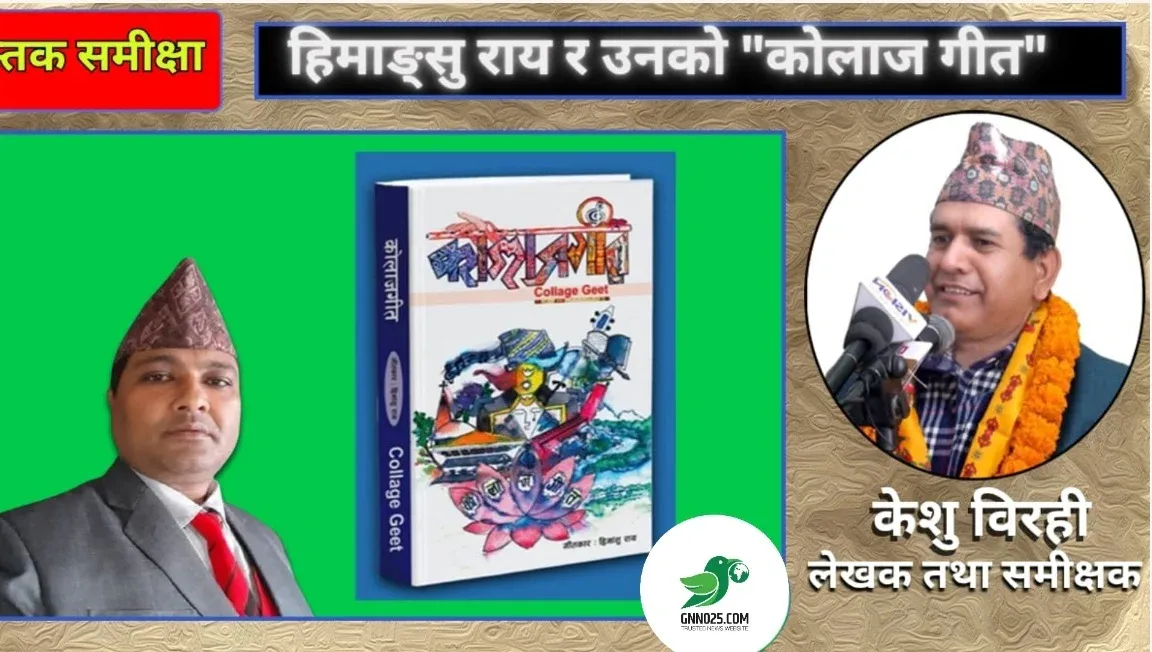

Himanshu Raya and His ‘Kolajgeet’

Keshu Birahi, Nepal : Himanshu Raya, who writes under the pen name ‘Kefas Aastha,’ is a familiar name in Nepali literature. Although he entered the world of publication relatively late, he has been an active and powerful voice in literary circles for the past three decades. Born on Baisakh 14, 2036 BS (April 26, 1979) in Saleri, Solukhumbu (now Solududhkunda Municipality–5), he is the second child of Jitendra Chandra Rai and Kalika Rai (Indira). In 2066 BS, he married Bhawani Basnet (Sarita), the eldest daughter of Ganga Prasad Basnet and Dambar Kumari Basnet of Ramechhap. They currently have two children: Utsav and Aarogya.

Originally from Basantatar VDC-5, Dhankuta (now Chaubise Rural Municipality–8), he moved from Sunsari’s Dharan-4 to Dangihat VDC-5, Morang (now Belbari–11, Laxmi Marg), where he resides permanently. Himanshu Rai is actively involved with various literary organizations, including Sungabha Sahitya Samaj, Lyricists’ Association of Nepal, Nepali Writers’ Association, Nepal Cultural Federation, and Belbari Pragya–Pratishthan. He has received various honors and awards, most notably the ‘Jagat Mardan Thapa Best Lyricist Book Award 2081,’ worth Rs. 57,000, awarded by the Lyricists’ Association of Nepal for his book Kolajgeet.

Raya made his formal literary debut with a poem titled “Taruni Jun” published in the wall magazine Prayas on Magh 8, 2051 BS from Dangihat–5, Morang. In addition to literature, he is also connected to journalism. While Kolajgeet is his first solo published collection of songs, many of his scattered writings have appeared in various magazines and newspapers. He has also contributed to collaborative publications and is known for his skills as a poet. I first came to know him as a poet, although he also writes ghazals, short stories, haiku, muktak, and devotional songs.

In 2076 BS, Kolajgeet was mentioned in Dadhiraj Subedi’s book Morangko Sahityik Itihas as being on the verge of publication. Again, in 2079 BS, Belbari Literary History was published. When I met him, I asked why the book that was said to be nearly ready in 2076 had not yet been released. His explanation was reasonable, so I continued to refer to it as an upcoming work. However, the long delay raised various questions—naturally so. Finally, in Bhadra 2081 BS, the book was published, answering all those questions. Since then, various discussions and new perspectives on lyrics have started to emerge.

Though lyrics are generally considered a sub-genre of poetry, many lyric enthusiasts argue that it is a distinct and significant genre of its own. Songs have been a part of human civilization since primitive times—sung while cutting grass, tending cattle, during births, marriages, and even funerals. The Lyricists’ Association of Nepal recognizes songs as one of the earliest and most important literary genres. Several song critics and analysts have also emphasized the need for deeper discourse on the subject.

Kolajgeet is a song collection published in 2081 BS, with Dipen Bantawa Rai as the publisher. The book includes forewords and messages from notable personalities such as former Nepal Academy Chancellor Bairagi Kaila, current Chancellor Bhupal Rai, Prof. Dr. Krishna Hari Baral, poet and academic Shrawan Mukarung, Nepal Cultural Federation president and filmmaker Tirtha Bahadur Thapa, former Lyricists’ Association president Chudamani Devkota, current president Basanta Bityasi Thapa, and Koshi Province president of Eastern Literary Academy, Pragyabibhushan Bibash Pokharel. A section titled “From the Pen of the Creator” features the author’s note.

The book has a total of 232 pages, including 204 core pages and 28 supplementary ones. Priced at Rs. 300 for individuals and Rs. 500 for institutions, the book contains 201 songs composed between 2049 and 2075 BS. Several songs like Yo Sansarma Paila Tekne, Yad Boki Banche Timro Saath Khoji Banche, Chaubandi Choli Ma Sajiye Muskurai Kaha Hidna Lageki, and Kin Aankha Rasauchha Ghari Ghari Yad Aauchha have already been recorded. Around a dozen and a half other songs from the collection have also been set to music. Himanshu also formed a local music group called The Eastern Band with seven fellow villagers and released a musical album titled Kosis around 2054/055 BS. His songs are highly regarded for their emotional depth, rhythm, and lyrical beauty.

Himanshu primarily enjoys writing modern folk songs. His lyrics explore diverse themes and reflect his talent for capturing a wide array of emotions and stories. He especially likes to write patriotic songs that are infused with the scent of his homeland. He deeply loves Nepal and views it as a sacred, heavenly place. His goal is to contribute to his soil and his nation. His profound love for the land is reflected in lines such as:

“My country, as beautiful as heaven,

I wish to die for it.

Covered in this soil,

I wish to do something for my country.”

(p.1, Swargajasto)

Nepal is a country blessed with natural beauty—from waterfalls, rivers, hills, to mountains. It also holds great religious significance, being a land of sages and seers. Yet, despite its beauty, corrupt politics has tainted the nation. In his lyrics, Rai praises the glory of Nepal and the Nepalese people. As he writes:

“How beautiful this creation, so full of wonder,

Overflowing with divine compassion.

The form of the omniscient Lord,

Shining among the poor and suffering.”

(p.5, Kati Sundar)

Love runs the world. Without love, nothing seems possible. Love brings light to life and leads us toward purpose. Many consider love the elixir of life. Rai’s lyrics often revolve around love, and his romantic songs have found much success. He expresses deep affection for his beloved—so much so that he wishes to lose himself in her memory. He writes:

“Don’t love me so much

That I forget myself.

Immersed in your memories,

I forget the world.”

(p.7, Yati Dherai)

Life is fragile. What is active today can be inactive tomorrow. Life can end without warning. Himanshu Rai addresses this truth seriously in his lyrics:

“Who knows when and where

This life will suddenly end.

When the time comes,

It picks you and wraps you in a shroud.”

(p.9, Thaha Nai Nadiei)

He doesn’t just write about love. He also addresses the pain of the poor and oppressed. Kolajgeet contains many songs that reflect the feelings of the underprivileged. Just as only the anvil understands the pain of the hammer, only a porter knows the pain of carrying heavy loads. Outsiders might think it’s easy, but climbing steep paths with a heavy burden is not simple. He writes:

“The porter carries

Pain with every load.

When I see his suffering,

My heart fills with sorrow.”

(p.148, Bhaari Bokne)

His songs cover a variety of themes—sometimes love, sometimes the purpose of life, and often the struggles of the poor. He reflects on life from hilltops and roadside rest stops, pondering the past and dreaming of the future. His lyrics mirror human emotions—love and hate, joy and sorrow, union and separation. His gentle words and imagery successfully convey human sensitivity.

The word Kolaj refers to a colorful, artistic composition. Given the variety of themes and artistic expression in his songs, the title Kolajgeet is apt. In essence, Himanshu Rai has successfully captured human emotions, offering readers rich lyrical nourishment. While the book’s cover, designed by local artist Shiva Chhangchha, may feel slightly ambiguous, its internal content and creative strength make it a strong and remarkable work. I am confident that this book will stand out, and I extend my best wishes for Himanshu Rai’s continued literary success.